COP26: need-to-knows about the upcoming climate shindig

Selva

5 min read

10/13/2021

Share

The Callendar effect

It’s been 83 years since a little-known British scientist called Guy Stewart Callendar published his research concluding that increased levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere are linked to higher global temperatures. Admittedly, he thought rising temperatures would be a good thing, a way of delaying a “return of the deadly glaciers”, but otherwise he was pretty much spot on with his findings.

In just a few weeks’ time, the world will gather in Glasgow for COP26, the latest in a long line of largely disappointing international climate jamborees, to again discuss what on earth we should do about this damn Callendar effect.

Wait, what actually is COP26?

John Kerry has hailed it as the “starting line for the rest of the decade” while Prince Charles calls it the “last chance saloon”. In more literal speak, it is the UN Climate Change Conference, known as COP26 (Conference of the Parties, 26th annual event), where leaders from nearly every country on the planet will sit and try to thrash out some agreements for international cooperation against climate change.

The conference kicks off on November 1st in Scotland’s most populous city, delayed a year thanks to the pandemic, and is expected to last for 12 days.

Whatever you want to call it, the hype around this one is reaching fever pitch and here’s why…

What’s the big deal with COP26?

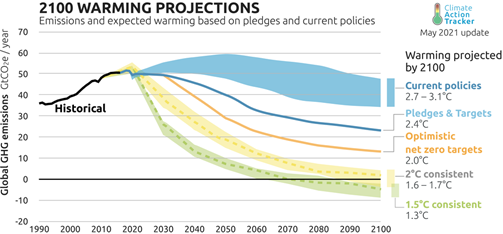

Well time is really running out for us as a species to get our shit together re climate change and sustainability. We need to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions by 45% by 2030, compared with 2010 levels, and get to net zero by 2050 to stand a chance of keeping warming limited to just +1.5°C. Given that emissions have risen nearly every year since the industrial revolution, halving them in just 9 years is an extremely tall order.

But what makes COP26 particularly important is that it marks the first five-year (well 6, thanks to the pandemic) milestone since the watershed COP21 event in Paris. Paris was hailed as a rare success in climate cooperation as it represented the first time ever that nearly every country in the world agreed to work together to limit global warming and set a target of limiting global warming to 2°C. It was one hell of a diplomatic and political achievement.

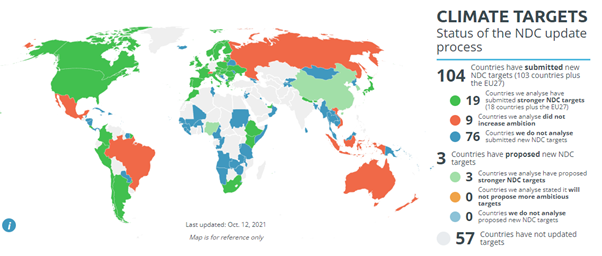

As part of the agreement, every country set its own national plans (know as NDCs, Nationally Determined Contributions) about how they would reduce their emissions. The combined NDCs agreed at Paris, however, were knowingly not nearly stringent enough to set us on a pathway for limiting warming below 1.5°C (the first tranche of NDCs was expected to lead to global warming of around 3°C), so the idea was that every 5 years countries update their NDCs with increasingly ambitious targets.

Those updates were due last year but several critical countries, including India and China, have not submitted theirs, while others such as Australia, Brazil and Russia have shown no increase in ambition compared with COP21. This doesn’t bode too well.

The hope is that COP26 will be the stage where big commitments are made, and momentous deals are struck, so that the world can finally bend the trajectory of emissions towards a 1.5°C compliant pathway. But don’t hold your breath, COP is all about politics politics politics…

What are the key sticking points?

Reaching agreements with so many different countries with wildly different priorities, stages of economic development, resources, diplomatic and economic power, and vulnerability to the effects of climate change is even more complicated than changing your mobile service provider. The current global energy shortages, and the reminder they bring that decarbonisation is not going to be easy, coupled with battered national finances thanks to the pandemic, won’t help matters.

Many previous COPs, including the last in Madrid, have ended in lackluster agreements or a load of hot air. More of the same this time around would be bad news for us all. These are some of the issues that will be keeping the delegates up at night.

1. Carbon markets – economic theory goes that if you put a price on something to create the right financial incentives, the invisible hand of the market will work its magic to reach the optimal quantity of supply demand equilibrium. In this case, the unit in the market is CO2, the optimal quantity is (net)-zero, and the estimated price for CO2 needed to reach net-zero is ~$150/tonne of CO2

So, put a price on carbon either through a tax or through a cap and trade system (which allow people to buy and sell “carbon credits” on a market) and let the incentives do the rest. Investment will go to where reducing and offsetting emissions is cheapest (i.e. carbon sellers), and the heaviest polluters in the rich world will pay the most (i.e. carbon buyers) .

Well, it’s a lot easier said than done. Some moderately successful carbon markets are already in place, including in the EU, but reaching an agreement on a framework for global cooperation on carbon markets will be hard to say the least. How on earth do you monitor and enforce compliance with rigorous accounting procedure for carbon emissions and offsets in different countries and industries all around the world? Regulation and compliance here would be an absolute nightmare, making it very hard for the market to establish credibility and effectiveness.

A framework with carbon markets was supposed to be agreed 3 years ago in Poland, and again in Madrid, but negotiations broke down, meaning that the can was kicked down the road to Glasgow.

2. Climate finance - the atmospheric CO2 balance is a global one. It doesn’t matter where CO2 is emitted, which makes the climate change challenge so unique. Back in 2009,developed nations committed to $100 billion per year by 2020 to help developing countries reduce their greenhouse gas emissions where it is likely to be cheaper than in the developed economies.

Effectively, richer countries pay to pick to the low hanging fruit of the global CO2 reduction options. Progress here has been slow too, with only $80bn of climate finance committed in 2019. At the very least, we’d hope to see a reaffirmation of this commitment, if not an increase.

3. Coal use and emission “fair shares” – the cheapest but dirtiest of all fossil fuels. Coal needs to be phased out of our energy mix ASAP and an agreement to this effect would be a major win. The problem is that many developing economics, most notably India and China, are still heavily reliant on coal for cheap energy for their economic development.

Fair enough. Today’s rich nations were built on abundant cheap coal and it is those rich nations that are responsible for most of the CO2 currently sitting in the atmosphere. Why should poorer nations reduce their emissions by cutting coal when the west has been getting rich by polluting the planet for decades? This is an intractable issue, don’t expect much of a breakthrough here.

There’s more - There are other key issues such as building processes to avert, minimize and address loss and damage caused by the consequences of climate change that will feature heavily on the agenda. We’ll also be keeping a beady eye on parallel talks for tackling biodiversity loss, restoring natural ecosystems and protecting the oceans.

What we’re trying to say is…

It’s in our nature to be optimistic and we believe progress will be made at COP26 but the hurdles are ohhh so high. The only things higher are the stakes. We need bold commitments, concrete milestones and policies (both short and long term), and the big powers in the room to show some humility.

We’ll keep you updated on how the talks progress via our Instagram page and check back here after the conference for our take on what unfolds…

How can you get involved

Climate action isn’t just for big business and government; we all have a role to play. You could go up to Glasgow and throw eggs at politicians but we have a better idea. Join Selva to become part of the solution by helping us to reforest the planet. Tree planting is agreed by climate scientists, the UN, and anyone else with half a brain cell as being a key solution in reducing global atmospheric CO2 level. Plant yours today.