COP26: the bare necessities from the mother of all political undertakings

Selva

5 min read

11/15/2021

Share

Stock take

A few weeks ago, we wrote how this year’s COP was being billed as “our last best hope” and the “starting line for the rest of the decade”. But, ultimately, COP is politics. Politics, the practice of making decisions in groups, is rarely easy, and COP is the kind of politics that makes Brexit and trade wars seem like negotiating which Netflix show to watch with your girlfriend on Sunday night. Reaching a unanimous agreement with almost every country on the planet, each with wildly different stages of development, resources, internal politics etc, about how to structure the future of the economy is no mean feat and cause for celebration.

Yes, there will be disappointment about the last-minute watering down of various texts related to coal and fossil fuel subsidies, and that more concrete, ambitious policies weren’t agreed to, but previous failures in climate diplomacy left too much to be done this time around. India and China are taking the blame for some 11th hour changes to the final text, but we have limited moral authority to sit in ivory towers that we built with steel, cement and coal and berate these countries for not doing more.

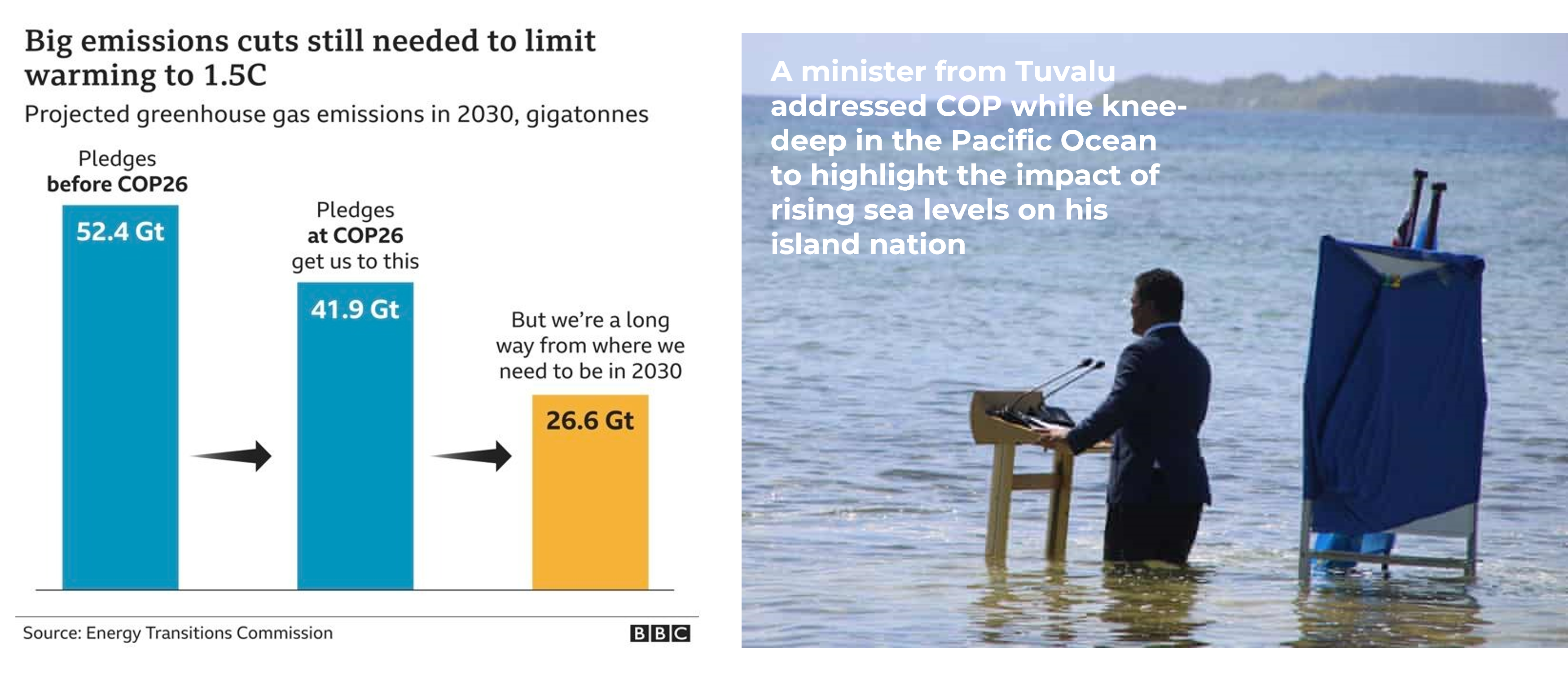

It was always going to be hard for COP to live up to the fanfare and become the messianic, watershed event that changes the course of our future. It certainly fell short of what was needed: previous commitments had us on track for 2.7° warming, after Glasgow we're on track for 2.4°, a long way from the 1.5° targeted, and that’s assuming countries do what they promise. But it’s a big step in the right direction, and an important shot in the arm of a difficult and long process.

What went well

Let’s start by looking on the bright side. There is plenty to be optimistic about, not least the improved rhetoric and the sense that politicians are finally starting to grasp the severity of the situation. For example, no previous COP agreements ever made mention of reducing coal use. It’s inclusion in the text of the Glasgow Climate Pact, albeit in the form of “phasing down” rather than “phasing out” coal, is progress. Over 40 countries agreed to wean themselves off coal entirely, including major burners like South Africa and Poland.

The US and China bilateral declaration, while light on details, is indication that world’s two largest emitters are trying to rise to the challenge. Say what you want about China, but it is usually very effective at doing what it sets out to do (e.g. poverty eradication), that gives us hope. All countries will now strengthen their emission reduction commitments again and come back next year to explain what they are doing between now and 2030 to align themselves with a 1.5° scenario. This forces immediate and tangible action.

The scourge of deforestation took centre stage with a landmark agreement that promised to end the destructive practice by 2030. Signatories included the hosts of huge forests like Brazil, Indonesia and Russia. Furthermore, a pact among many nations to reduce methane emissions, a potent greenhouse gas, by 30% by 2030, is a big win.

The development of carbon markets also saw some progress. Pricing carbon through carbon markets is seen a crucial tool by economists to help align the incentives of capital providers with the needs of the environment, but developing a global market with consistent standards that is transparent and accountable has proved to be extremely complicated. New rules agreed at COP26 seem to have broken this impasse and created a common framework that could unlock huge amounts of finance to flow towards emissions reduction schemes like forest protection and low-carbon power projects. There is skepticism, however, and critics point to a carbon trading system that was previously established as part of the Kyoto Protocol in 1997 and was plagued with corruption and ineptitude.

All these agreements have their pitfalls and of course mean nothing unless they are put into practice in the spirit in which they were intended. However, there is undoubtedly improved urgency and heightened ambition. Is it enough? Probably not, but let’s not make perfect the enemy of the good.

What didn’t

There is understandable disappointment that the summit didn’t yield some of the game-changing agreements that are needed to address the scale of the challenge. Cutting global CO2 emissions in half in ten years is a monumental challenge that requires equally monumental changes. These changes are absent and 1.5° is, it pains us to say, almost out of sight.

As a species we have procrastinated too long. Every year that we have delayed has meant sharper and sharper cuts would be needed to get to net-zero by 2050. We’ve left it late and relied on an impossible Hail Mary to get us out of trouble.

We were hoping for a quick phase-out of coal: we got a “phase-down”. We were hoping for large re-commitments related to the amount of climate finance that rich countries send to poor countries for adaption and emission reductions: we got vague and open-ended platitudes. We were hoping for global cooperation on the mother of global challenges: we got no-shows from Russian, Chinese and Brazilian heads of state. We were hoping for leadership from the US: they didn’t even sign up to an agreement to end coal use, while 40 other countries did. We were hoping for high-level discussions about the importance of our diets (given that agriculture is responsible for ~30% of global GHG emissions): instead, punters at COP were served beef burgers and haggis. As the co-founder of a plant-based meat company put it, serving meat at a climate change summit is like handing out cigarettes at a cancer conference.

High on the list of priorities prior to the summit was the issue of climate finance and “loss and damage”: rich countries paying poorer countries to help reduce their emissions and as compensation for the damage they are already experiencing due to climate change. Many developing countries left disappointed that no concrete agreement was reached on such compensation and that the re-commitment to a previous, unfulfilled pledge to provide $100 billion annually was left vague (the money promised would be provided “as soon as possible”).

So, what now?

The work has only just begun. Countries must now expedite the implementation of emissions reduction policy and prepare for next year’s strengthened commitments. Promises must turn into practice. Momentum needs to be seized. Greta Thunberg has to find a bigger swear jar.

If the previous 26 COPs have shown us anything it’s that we can’t rely on governments and big businesses to do it all. We must start with ourselves. Blaming politicians and corporate execs for our current predicament is hiding from the uncomfortable truth that it is our individual day-to-day actions that drive the economy. Businesses make what we buy, and politicians act to please our whims. If you’re unhappy with the results of COP, if you’re unhappy with the direction that we’re heading in, then, to borrow a phrase, start with the man in the mirror. There are no politics there.